Over the years I have acquired this rather pretentious past-time of reading scholarly articles about different topics, esoteric or otherwise. I have read academic papers on astronomy, tropical cyclones, Korean pop culture — so basically anything that I find vaguely interesting.

I usually go to Google Scholar to find these articles. Google Scholar works just like regular Google, except when you enter your keywords, the database shows you a list of research studies written by various experts from different fields. It’s not as boring as it sounds, to be honest, especially if you search for topics that you’re genuinely interested in.

The other day, for instance, I was looking for articles about my hometown and I found a study on the variations of Sorsogon dialects in the context of teaching math in grade school. The study was done after the K-12 program mandated the use of the students’ mother tongue for teaching basic subjects between kinder and Grade 3.

It was news to me. I did not know that kids these days have to learn math in their local languages. Math is a highly technical discipline and I have always articulated its concepts in English. Most of us have, haven’t we? We all say “one minus one”, for example, and — how do they even translate this to Bicol anyway?

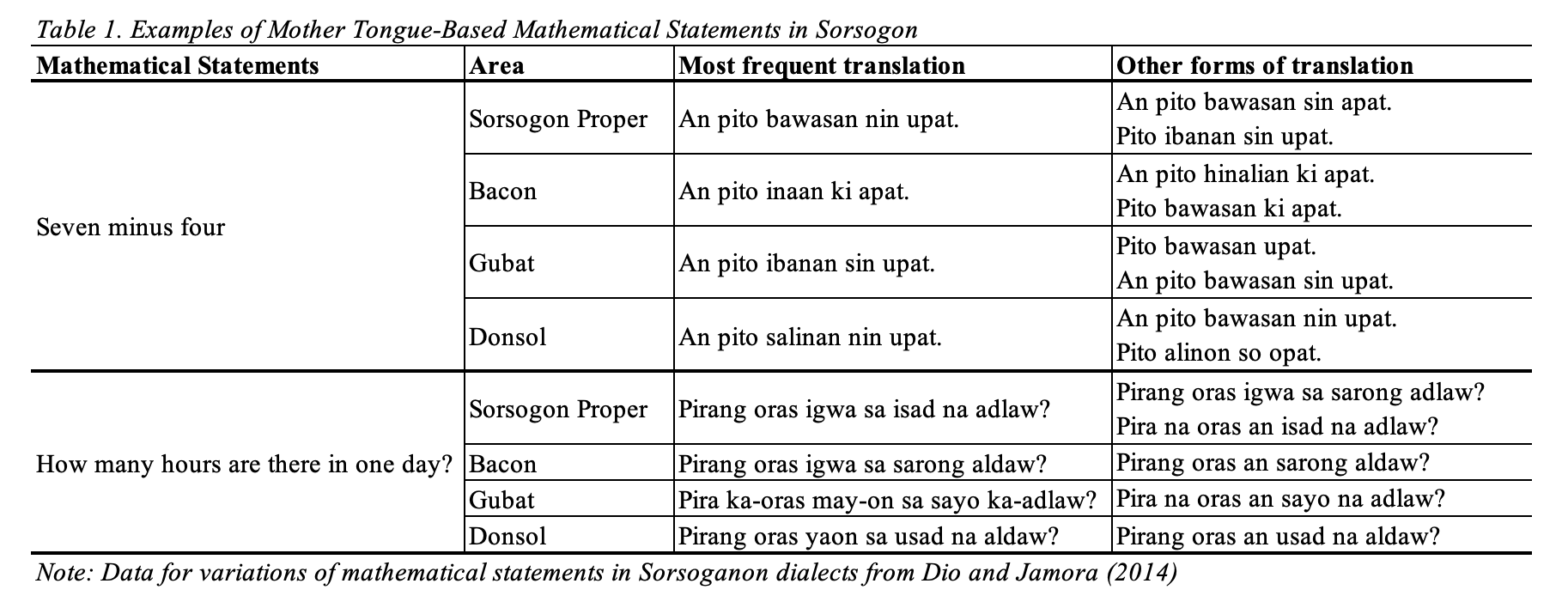

The examples in Table 1 were taken from an article by Ryan V. Dio and Michael John A. Jamora published in 2014. Dio and Jamora divided the Sorsogon dialects into four categories based on four major areas, and they collected the most commonly used translations of mathematical statements based on interviews with teachers.

The teachers who participated in the study observed that their students were more participative in class after the medium of instruction had been changed to their mother tongue (p. 114). It tracks, doesn’t it? Back then my classmates and I never spoke to each other in English or Filipino. We always spoke in Bicol, and it just makes sense that kids are more willing to raise their hands and share their answers in a more familiar language.

I also noticed that certain areas in Sorsogon formally use the word “sayo” instead of “saro.” The study even lists “sadiyot” and “mabûgat” as valid variations of the words “saday” and “magub-at”, respectively (p. 112).

I always thought that “sayo”, “sadiyot”, and “mabûgat” were verbal ticks of my grade school classmates who were yet to figure out how to speak properly. You know how parents say “wiwi” instead of “ihi” to their kids? I thought “sayo” was just a cutesy way of saying “saro”, but apparently there are municipalities in Sorsogon that use those words on the daily.

Another feature that stood out to me was the phonetic length of the local translations. The Bicol translations simply take longer to enunciate compared to their English counterparts. The word “minus”, for example, only has two syllables while “bawasan nin” has four. A classmate once told me that Chinese kids are good at math probably because counting in Mandarin is phonetically quicker. I don’t speak Mandarin so I have no clue if he was pulling shit out of his ass, but it kinda makes sense, doesn’t it?

Anyway, phonetics wasn’t even a big deal at this point. The study noted that one of the top challenges for teachers was the limited availability of teaching materials (p. 114-115). The study found that the teaching guides distributed across the region were primarily written in Bicol Naga. Teachers from other parts of Bicol therefore had to write their own translations so they could match the materials to the dialects in their respective areas. (Teachers really deserve a pay raise, ‘no?)

The teachers interviewed for the study also raised concerns regarding math terms that “should not be translated” (no specific examples were given) and the lack of a standardized translation guide. The study reported that standardized exams on the division, regional, and national levels were not always written in the same lexical variant taught in a given district, causing confusion among students.

This study is about five years old so maybe all those issues have already been addressed since then. It proves, however, that at least this specific feature of the K-12 program was prematurely implemented. The effectiveness of the K-12 policy as a whole is an entirely different discussion.

And ‘yun, that’s it. I wonder if any of you actually read the entirety this post. Every now and then I feel the urge to blabber about things that I know only a few would appreciate, but hey, blog ko naman ‘to a? Charet.

Ryan V. Dio and Michael John A. Jamora wrote “Variations of Sorsogon Dialects as Mother Tongue-Based Medium of Instruction in Grade School Mathematics” which was published in the Asia Pacific Journal of Education, Arts and Sciences (Volume 1, Issue No. 4) in 2014. I retrieved a PDF version of the article from this link.

The featured image is by Crissy Jarvis from Unsplash.

Leave a reply to rAdishhorse Cancel reply