I DID NOT know about the term “commonplace book” until I watched a YouTube video about it recently. A commonplace book, I learned, is a notebook in which a person records a smorgasbord of notes: an account of one’s day, a passage from a book, a recipe, a conversation, what-have-you.

As an auditory learner whose comprehension of the world and beyond relies heavily on verbal articulation: Finally! A name!

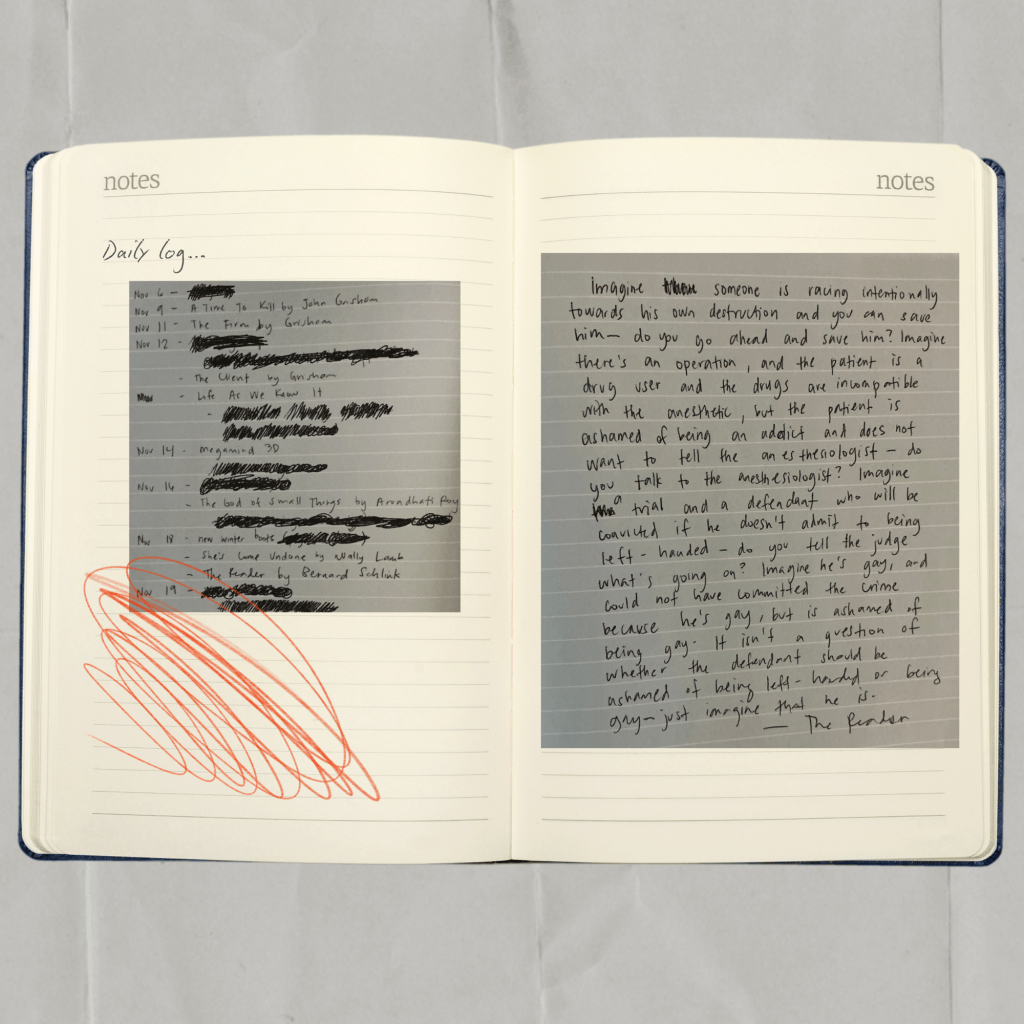

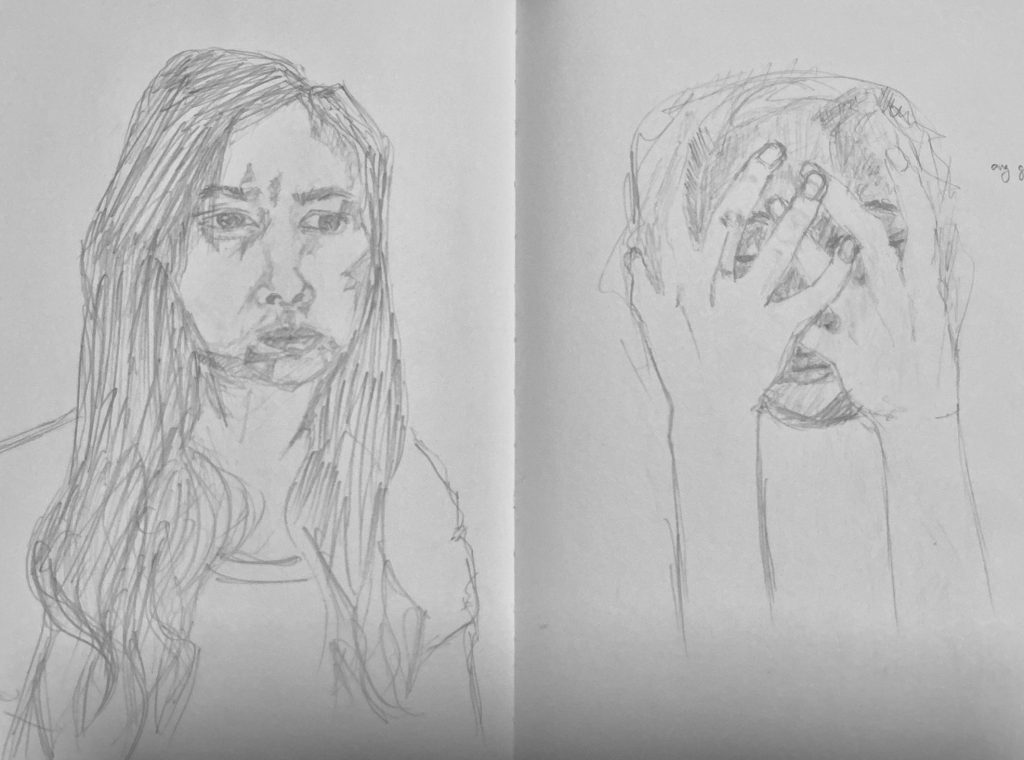

The journals that I’ve kept since I started writing on paper are a Frankenstein patchwork of a diary, a sketchbook, a scrapbook, etc. They’re neither this nor that, so the best category to slip them under is, well, the Commonplace Book.

I feel validated knowing that there’s a term for how I keep a notebook. It tells me that my inability to stick to a consistent structure is not a deficiency in my mental faculties or a flaw in my personality.

People have been commonplacing for centuries, apparently. Sei Shonagon’s The Pillow Book is a proto-commonplace book, and the Japanese calls this genre “zuihitsu” or “following the brush.” John Locke also wrote an entire methodology for keeping commonplace books in 1685 — who knew? (Not me.)

The practice itself originated way before Seijo and Locke. Rhetoricians of the classical antiquity era used commonplacing as a technique to store ideas that they could later use in debates and speeches. Back then, philosophers filed ideas specifically for easy retrieval and reference.

The term “commonplace book” only became prevalent during the Renaissance. Following the spread of printed books in Europe, writers and readers started copying into their notebooks the passages that they found insightful, much like how a chronically online geek of today (or of the 2010s) would “reblog” a post on Tumblr or “pin” something on Pinterest.

There is no universal structure for curating a commonplace book. Although Locke’s 17th century treatise popularized the indexing method — and it has likely influenced the format of present-day notebooks such as the Leuchtturm1917 Notebook Classic — having an indexed journal is not a requisite for commonplacing.

The commonplace book is simply a notebook that acts as a personal encyclopedia for the things that one has deemed worth writing down. Writers use it as a helpful reference tool; philosophers use it as a study material.

People like me, however — people who do not visit the agora every day wearing an airy robe to debate with fellow bearded men — we keep a commonplace book out of pure compulsion to jot things down.

“The impulse to write things down is…inexplicable to those who do not share it, useful only accidentally, only secondarily, in the way that any compulsion tries to justify itself,” writes Joan Didion. “Yep,” says me.

It’s not always about the desire to record how facts took place; sometimes it’s about the impulse to avoid the potential regret of not having done so.

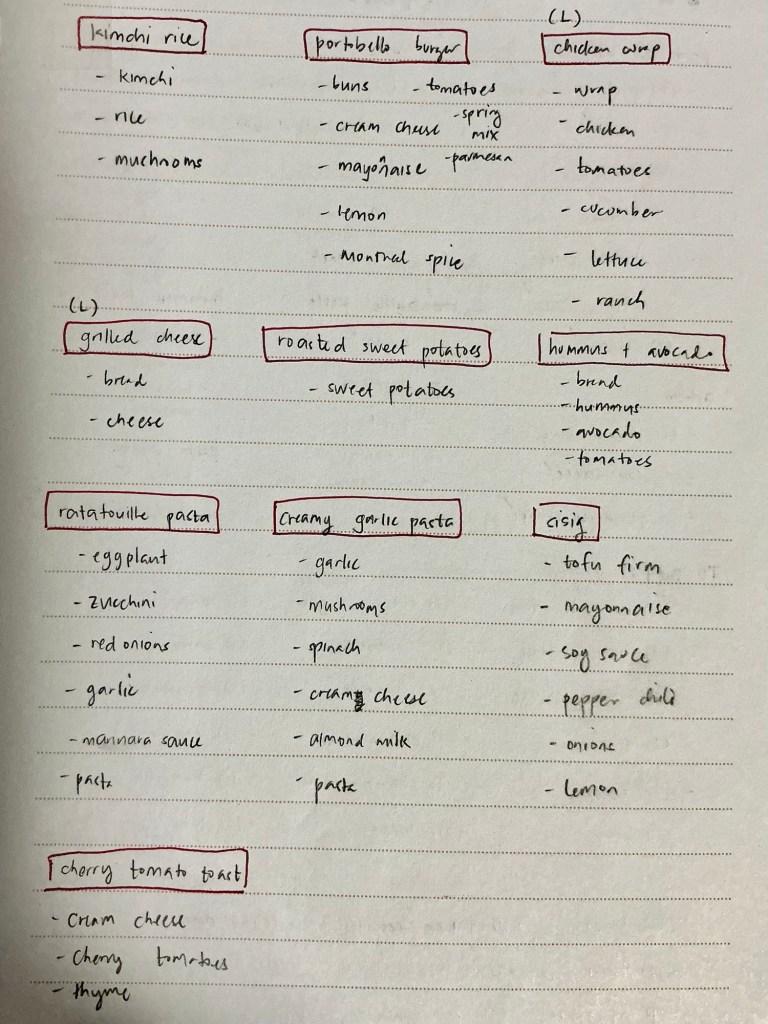

I have written down ingredients for easy-to-make dishes because of the ever-familiar struggle of deciding what to cook for supper. I have listed reasons for why I wanted to quit a job — helpful not only for job interviews, but also during moments when I feel somber about being a corporate peon. I have also kept lengthy descriptions of how a wonderful day had gone, lest I forget that life is and can be good.

Now that I have a name for my erratic journaling practice, I get to appreciate the beauty of its capriciousness. The notes are either flowy entries or little fragments. The drawings are often uncaptioned. Everything is in analog form created for nobody else’s consumption but my own.

My commonplace journals are not a stage on which I perform. They are a collection of candid snapshots of who I was at different instants in time, each veiled by the opacity of a past I can now only perceive through the bias of the present.

Some pages draw me back to the days when I felt drained by the sheer practice of living. The very act of reading/seeing/re-witnessing them reminds me that, somehow, I have managed to escape every rut I’ve ever fallen into. This gift of hindsight is empowering.

I only have several pages left in my current commonplace book. Fifteen and a half leaves to be exact, and I am already excited to begin the next one. I might try following Locke’s method of indexing, or I might just continue my unstructured, que sera sera approach.

As with many, many things in my life — I will never truly know until I get there.

Further Reading/Watching:

[1] you should keep a commonplace book (& how) (Oddly Specific Crystal)

[3] A Short History of Commonplace Books (Gloucestershire Guild of Craftsmen)

[4] Digital commonplacing by Jon Hoem and Ture Schwebs

Leave a reply to coolpeppermint Cancel reply